More Information

Submitted: December 05, 2025 | Accepted: December 18, 2025 | Published: December 19, 2025

Citation: Pandey N, Dhyal V, Agarwal B, Aarshiya. Crime and the Subconscious Mind (How Hidden Childhood Memories Trigger Violent Behaviour). J Forensic Sci Res. 2025; 9(2): 230-243. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jfsr.1001108

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jfsr.1001108

Copyright license: © 2025 Pandey N, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Childhood trauma; Subconscious mind; Implicit memory; Neurocriminology; Emotional regulation; Shadow psychology; Repetition compulsion; Trauma-informed rehabilitation

Crime and the Subconscious Mind (How Hidden Childhood Memories Trigger Violent Behaviour)

Nyasa Pandey*, Vishal Dhyal, Bhoomi Agarwal and Aarshiya

Gehlot Sadan, Hazaari lal Meena 17 Shiv Nagar Vistaar Colony, Ramnagariya, Jagatpura, Mahadev Nagar Vistaar Colony, Jaipur , Rajasthan 302017, India

*Corresponding author: Nyasa Pandey, Gehlot Sadan, Hazaari lal Meena 17 Shiv Nagar Vistaar Colony, Ramnagariya, Jagatpura, Mahadev Nagar Vistaar Colony, Jaipur , Rajasthan 302017, India, Email: [email protected]

Crime is often understood through conscious intent, rational decision-making, and environmental influences, yet a substantial body of psychological and neuroscientific research demonstrates that many criminal behaviours originate from subconscious processes shaped during early development. Subconscious or implicit memories—formed through nonverbal, emotional, and sensory experiences—persist outside conscious awareness but continue to influence perception, affect regulation, and behavioural responses. Traumatic childhood experiences, insecure attachment, and chronic stress become encoded in these implicit memory systems, creating automatic patterns of reactivity that can manifest as aggression, impulsivity, or compulsive offending in adulthood.

This review synthesizes findings from developmental psychology, neurocriminology, trauma science, and psychodynamic theory to explain the mechanisms through which subconscious memory contributes to criminal behaviour. These mechanisms include pattern completion, where present cues reactivate emotionally charged childhood templates; amygdala-driven threat responses that precede conscious awareness; and repetition compulsion, in which individuals unconsciously re-enact unresolved trauma. Neurobiological studies further show that offenders with trauma histories often exhibit hyperreactive limbic systems and reduced prefrontal regulatory control, increasing vulnerability to trigger-driven violence.

Beyond causation, this review highlights important forensic implications, including the need for trauma-informed assessments, recognition of dissociation and emotional triggers, and careful interpretation of memory reports in legal contexts. Additionally, emerging therapeutic approaches—such as EMDR, reconsolidation therapies, and emotion regulation interventions—offer promising pathways for rehabilitation by targeting the implicit memory networks that underlie maladaptive behaviour.

Overall, understanding the subconscious foundations of crime expands the scientific and forensic perspective, emphasizing early intervention, psychological integration, and evidence-based rehabilitation to reduce recidivism and promote long-term behavioural change.

Crime has traditionally been explained through rational decision-making, social learning, and environmental pressures, assuming that individuals consciously weigh risks before engaging in unlawful behaviour. However, modern psychological and neuroscientific research suggests that a large portion of human behaviour—including criminal actions—is shaped not by conscious reasoning but by subconscious processes that operate automatically and outside of awareness. These latent processes, established early in life and consolidated across development, inform the way in which individuals perceive threats, modulate their emotions, and behave in times of stress or conflict.

The subconscious mind is primarily sculpted by implicit memories, or the emotional and sensory experiences that were stored during early childhood before the brain has fully developed language and reasoning abilities [1,2]. When early life experiences include neglect, trauma, rejection, or chronic stress, the brain stores these experiences as strong emotional templates. When similar cues are present later in life, the templates can be activated through automatic pattern matching and result in reactive aggression, fear responses, impulsive acts, or violent outbursts-even when the individual has no conscious awareness of the source for these reactions [3].

The emerging research in neurocriminology further supports this view. For example, studies show that subcortical structures, such as the amygdala and hippocampus, often respond to perceived threats milliseconds before conscious awareness of those threats emerges [4].

Emerging research in neurocriminology further supports this view. Studies show that subcortical structures like the amygdala and hippocampus often respond to perceived threats milliseconds before conscious awareness emerges. At the same time, impairments in the prefrontal cortex—responsible for judgment, self-control, and moral reasoning—reduce an individual's ability to regulate these automatic reactions. This imbalance between emotional reactivity and cognitive control creates a pathway where unresolved childhood trauma and subconscious memory systems contribute directly to impulsive or violent criminal behaviour [5,6].

Psychodynamic and analytical theories provide an additional layer of insight. Jung’s concept of the shadow suggests that rejected or repressed aspects of the personality may resurface in harmful ways when left unintegrated. Similarly, psychoanalytic researchers describe repetition compulsion, where individuals unconsciously recreate unresolved childhood conflicts or traumas through their actions—even when those actions are destructive or criminal. These perspectives align with modern trauma research showing that individuals may unconsciously reenact emotional patterns that were never processed or resolved.

This review aims to integrate these multiple perspectives—psychological, neuroscientific, and psychodynamic—to explain how subconscious memory influences criminal behaviour. By examining the hidden mechanisms linking early childhood experiences to adult offending, the paper highlights the importance of trauma-informed assessment, early intervention, and rehabilitation strategies that target deeper psychological processes rather than focusing solely on conscious decision-making [7]. Understanding these pathways not only provides a more accurate explanation of crime but also guides more effective avenues for prevention and long-term behavioural change.

Unconscious criminal motivations: Claims regarding casuality between childhood trauma and violent behaviour

Establishing causality: Beyond correlation

While early research often described childhood trauma and violence as merely correlated, longitudinal and prospective studies now provide strong evidence for a causal developmental pathway. These studies demonstrate that exposure to abuse, neglect, or chronic stress during sensitive periods of brain development precedes and predicts later violent and impulsive offending, even after controlling for socioeconomic status, intelligence, and parental criminality. A central causal mechanism lies in neurodevelopmental disruption. Chronic childhood stress alters the maturation of fronto-limbic circuits, producing heightened amygdala reactivity and weakened prefrontal inhibitory control. This imbalance increases the probability that emotional arousal will translate into impulsive or aggressive behaviour rather than regulated responses.

Longitudinal evidence supporting a causal link

Prospective cohort studies following abused children into adulthood provide some of the strongest causal evidence. Individuals exposed to documented childhood maltreatment show significantly higher rates of violent arrests and convictions decades later, suggesting that trauma is not merely associated with violence but contributes to its emergence over time. Notably, this increased risk persists even when individuals are removed from abusive environments, indicating that early neuropsychological imprinting, rather than ongoing exposure alone, drives later violent tendencies.

Dose–response relationship: Trauma severity and violence risk

A key criterion for causality is the dose–response effect, which is consistently observed in trauma research. As the number and severity of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) increase, so does the likelihood of violent behaviour, aggression, and criminal recidivism. Individuals with multiple forms of abuse (e.g., physical abuse combined with emotional neglect) show disproportionately higher levels of reactive aggression compared to those exposed to a single stressor. This gradient strongly supports a causal interpretation rather than a coincidental association.

Neurobiological mediation of trauma-driven violence

Neuroimaging studies strengthen causal claims by identifying biological mediators between childhood trauma and violent behaviour. Trauma-exposed individuals consistently show:

- Hyperactivation of the amygdala to perceived threat

- Reduced volume and functional activity in the prefrontal cortex

- Impaired connectivity between emotion and control systems

These neural alterations precede behavioural outcomes and explain why violence often emerges as impulsive, disproportionate, and poorly regulated, rather than premeditated.

Integrative causal model

Taken together, the evidence supports a developmental–neurobiological causal model consistent with the arguments advanced in your review article. Childhood trauma initiates long-term changes in emotional learning, threat perception, and impulse regulation. These changes function below conscious awareness, increasing vulnerability to violent reactions when individuals encounter stress, rejection, or perceived threat later in life.

Importantly, trauma does not act as a deterministic cause of violence. Instead, it raises the probability of violent behaviour by weakening regulatory systems and strengthening automatic emotional scripts—precisely the mechanisms discussed throughout your paper.

Early childhood imprints and their long-term psychological impact

A large part of human affective development occurs during the first seven years of life, a period during which the brain is highly plastic and predominantly encodes experiences through implicit and subconscious rather than conscious and verbal [2,8]. Negative early experiences like emotional neglect, harsh discipline, exposure to domestic violence, or insecure attachment can shape the child's inner world in profound ways. Because these experiences happen before the development of reasoning and language, they get stored as emotionally charged impressions, somatic sensations, and behavioural patterns rather than explicit narratives as such, as van der Kolk puts it [3].

These implicit emotional templates thereafter influence how an individual makes sense of social interactions, reacts to stress, or processes conflict. For example, a child who grows up in an environment of unpredictable aggression internalizes fear, hypervigilance, and mistrust as default modes of functioning. Later in life, similar trigger signals (e.g., loud voices, criticism, or rejection) can automatically activate these same early memory networks, resulting in acute emotional response or impulsive aggression [5]. Often, this activation operates unconsciously; many offenders relate that their violent outbursts were triggered “out of nowhere” or describe feelings of “watching themselves” act uncontrollably.

Modus by which subconscious memories guide criminal activity through automatic mechanisms

a. Emotionally Provoked Reactivation: Subconscious memories represent pattern matching or pattern completion, where the brain is responding to current cues that share aspects of the traumatic situation [9]. The cues may be subtle: a voice tone, a facial expression, or a relational dynamic. With this cue triggered, the brain reactivates the entire emotional response related to the original memory—anger, fear, shame, or helplessness—without the person understanding why it's happening.

This may lead to watching for sudden aggression

- loss of emotional control

- Dissociative or “blank-out” moments

Thus, an apparently minor provocation may trigger a disproportionate emotional and behavioural response stemming from early trauma, not the present situation.

b. Difficulty in emotion regulation and attachment disruptions: Children deprived of predictably supportive relationships in their early years generally develop maladaptive attachment styles, such as anxious, avoidant, or disorganized attachment. Main & Solomon, 1990 [10]. These attachment styles are not just ways of relating, but also influence how the nervous system responds to stress over a lifetime. Adults with disrupted attachment may commonly display:

- Low distress tolerance

- Hope for abandonment.

- Increased rejection sensitivity

Zeal: •TAGGRESSIVE OR SELF-PROTECTIVE RESPONSES TO PERCEIVED THREATS

These emotional vulnerabilities significantly heighten the possibility of reactive violence, especially in intimate relationships or high-stress situations that Dutton discussed in 2007.

c. Shame, befindlichkeit, and its transformation into aggression: A common psychological mechanism among offenders is the acting out of internalized shame as externalized anger or violence. If early experiences have produced a profound sense of humiliation or worthlessness, then anything that serves as a reminder in later life, criticism, disrespect, or failure, can stimulate old emotional injuries that have lain unseen. Because shame is an exceptionally intolerable emotion, those who feel ashamed may externalize it as aggression in defense. This phenomenon explains:

- Why some offenders react explosively even to minor insults

- Why violence could feel "relieving" or emotionally numbing

- Why some crimes seem illogical or disproportional to the trigger

Reactions like these reflect not a rational criminal motive, but rather an emotional wound surfacing from childhood.

The "unconscious script" behind violent behaviour

The majority of violent offenders do not premeditate their acts; rather, they commit unconscious emotional patterns, often called “unconscious scripts” or implicit behavioural templates [3,11]. These scripts are shaped during early childhood and continue to influence adult behaviour without the individual fully realizing it. In simple terms, the subconscious mind stores memories, emotions, and relational experiences in a nonverbal form, and these stored patterns later guide how a person reacts to conflict, threat, power, rejection, or shame.

1. How unconscious scripts form in childhood: The brain learns emotional and relational rules during early childhood through repeated interactions with caregivers. If early experiences are traumatic, inconsistent, neglectful, or violent, the child forms implicit emotional expectations such as:

- “People who love me might hurt me.”

- “Conflict is always dangerous.

- “I have to defend myself; it's self-defense.”

- "Showing weakness leads to punishment."

- “Aggression is the only way to gain control.”

These beliefs are not consciously thought; they become automatic emotional reactions encoded into the nervous system, as was earlier suggested by Schore [8] and Siegel [2]. By the time this child reaches adulthood, these patterns function like "scripts" shaping responses to stress or interpersonal tension.

2. How these scripts are activated during violent behaviour: When a current situation 'rhymes' with an old emotional wound—such as rejection, humiliation, being ignored, threatened, or criticized-the subconscious script activates in the instant. The trend is usually of the form:

a. Emotional Trigger → Pattern Activation

A small present-day event -a comment, a tone of voice, a partner walking away-matches aspects of the unresolved childhood memory.

It fills in the emotional context unconsciously.

b. Emotional Overload

The individual experiences intense emotions such as fear, shame, or rage that feel “out of proportion” to the situation. This is because they react not to the present moment but to their past.

c. Identity Change

Others describe the feeling of being a different person, sometimes entering into a “fight mode” or “losing control.” This is because trauma scripts override logical reasoning.

d. Impulsive or Violent Action

The person acts out the script through:

- Aggression

- Threatening behavior

- destruction

- self-defense reactions

- Violence in intimate relationships

The behavior is usually characterized by being automatic or irresistible.

e. Post-Action Confusion

Following the incident, many criminals report:

- “I don’t know what came over me.”

- “It felt like I was watching myself.”

- "It happened so fast."

This indicates a disconnection between conscious awareness and subconscious emotional regulation.

3. Examples of unconscious scripts leading to violence

a. Abandonment Script

A person who was neglected or abandoned as a child may perceive a partner walking away during an argument as a life-threatening event.

Triggers alarm and outrage → leads to the end. Assault, threat, or destruction.

b. Humiliation Script

A child who experienced shaming or public ridicule may grow up hyperreactive to disrespect. Old wounds are activated and, therefore, minor insults set off explosive anger. c. Control Script Children who grow up in chaotic or unsafe homes often equate control with safety. As adults, when they feel powerless, they may use aggression to regain a sense of control. d. Repetition Compulsion Script: Some individuals unknowingly reenact their childhood trauma. Example: A person abused by a caregiver may reenact the role of the aggressor as an adult offender. This is not intentional—it is a subconscious attempt to “master” or make sense of the old trauma.

4. Why offenders repeat the same crimes: The psychological explanation

Violent and impulsive offenders often show repetitive patterns in their crimes.

This is because the subconscious script becomes familiar and emotionally “automatic,” even if harmful.

Psychologists describe this as:

- repetition compulsion

- trauma reenactment

- implicit relational patterns

It deals with internal working models.

These mechanisms explain why some offenders commit similar crimes under similar emotional conditions.

5. Forensic importance of understanding unconscious scripts

Identifying unconscious scripts aids a forensic psychologist in recognizing:

- Why some crimes appear unplanned

- Why violence escalates from small triggers

- Why offenders repeat the same harmful behaviour

- Why rational accounts usually fail

- Why do many offenders struggle to explain their motive

Forensic and rehabilitation implications

The more important consequence is knowing how subconscious memories and unresolved childhood experiences influence violent behaviour. Understanding this could have major implications for forensic psychology and criminal justice. Many offenders do not act with full conscious intent; rather, their actions are often driven by emotional responses to triggers.

Responses rooted in trauma, fear, shame, or abandonment learned early in life. These reactions can be sudden, overwhelming, and difficult for the person to explain, which means that traditional forensic assessments mainly focus on deliberate planning, rational motives, and situational factors, and may miss the deeper psychological mechanisms of the crime.

By knowing the subconscious processes, forensic professionals can gather a more precise picture of the offender's motivations and internal vulnerabilities.

From a legal perspective, the presence of trauma-driven or subconscious reactions does not absolve an offender of responsibility but rather provides important context for the evaluation of intent, emotional capacity, and culpability. There is increasing recognition by the courts that childhood trauma and emotional dysregulation may contribute to poor impulse control, distortion in threat perception, and lower capability to engage in reflective decision-making occurs during high-stress incidents. Understanding such factors helps explain the difference between planned violence and impulsive, trauma-triggered reactions, and offers the prospect of more informed decisions about sentencing, mitigation, and the need for psychological intervention. This perspective acknowledges fairness without excusing harmful actions.

These insights also have profound implications for rehabilitation. Most correctional programs rely heavily on cognitive interventions such as anger management or CBT, which aim to change conscious thoughts and behaviours. However, if the violence results from implicit emotional scripts from trauma, then cognitive strategies by themselves cannot succeed because they do not reach the subconscious emotional networks that are driving the behavior. Rehabilitation must target the emotional roots of aggression through trauma-focused therapeutic approaches like EMDR.

The methods include trauma-informed CBT, attachment-based therapy, somatic processing, and memory reconsolidation approaches that work directly with the implicit memory system to decondition triggers and develop healthier emotional responses.

When rehabilitation programs address subconscious patterns rather than conscious reasoning alone, long-term behavioural change is much more achievable. Offenders with insight into their triggers and who have healed unresolved emotional wounds are significantly less likely to continue exhibiting the same harmful behaviours.

By integrating assessment for trauma, emotional regulation training, and implicit memory work into practice in forensic settings, the criminal justice system can more effectively prevent recidivism and support Actual rehabilitation, so to say. The approach, in general, gets transformed from punishment-based to root cause-based, creating safer results both for the individual and society. 3. Does the Criminal Brain Make Decisions Before Conscious Awareness? Neurocriminology Perspective represents a serious challenge to the traditional view that criminal behaviour always follows from conscious, voluntary choice. Modern neuroscience has demonstrated how the brain often prepares and initiates an act before a person consciously decides upon it. In emotionally arousing or threatening situations, this pre-conscious activity becomes even more dominating, above all in persons with trauma experiences or impaired emotional regulation abilities. These results indicate that certain criminal acts-particularly impulsive, reactive, or violent ones-can be the result of fast neural processes, rather than reflective thought. Understanding these mechanisms provides a deeper insight into why certain crimes occur suddenly, without planning, and why offenders frequently report acting “without thinking.”

Pre-conscious decision-making in the criminal brain

Studies using EEG and fMRI have found that the brain starts decision-related neural activity milliseconds to seconds before an individual becomes consciously aware that they are deciding to act. This implies that behaviour, mainly fast and emotionally charged, results from the subconscious parts of the brain long before rational thought is engaged. This can be explained in criminal scenarios where an individual may involuntarily react instantaneously in a hostile manner to perceived threats without taking his/her time to think over the situation.

The amygdala plays a critical role in this process. It constantly scans the environment for danger and initiates fear, anger, or defensive responses within a split second. For those who have experienced traumatic childhood events, chronic stress, or insecure caregiving, the amygdala becomes hypersensitive. In these cases, it strongly reacts to cues that others may perceive as harmless. Once activated, this automatic emotional rush sweeps through conscious awareness and propels the body toward action.

In these instances, the conscious mind may not be engaged at all. The speed of the emotional arousal allows little time for reflective judgment, and the responses are often impulsive, such as shouting, striking out, or escalating a confrontation. Offenders commonly report this experience as “blanking out,” “losing control,” or feeling the event occurred automatically. These phenomenological reports are supported by the neuroscientific evidence that pre-conscious processes can trigger behaviour before conscious intention forms. Thus, though the actions are real enough and result in consequences, the decision-making reflecting that behavior often originates outside conscious awareness.

Neural correlates of criminal impulsivity and aggression

While pre-conscious processing explains how fast actions are initiated, the differential aspects of the brain structure and function explain why some individuals are more prone to such impulsive actions. Two of the most important regions implicated in this circuit are the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. The amygdala is the emotional alarm system, whereas the prefrontal cortex is responsible for reasoning and impulse control, among other functions such as planning and moral judgment.

In many violent or impulsive offenders, the amygdala is overactive, reacting powerfully to perceived threats-even minor ones. This excess emotional arousal gives rise to powerful drive states-behaviors related to basic needs that insist on immediate gratification. At the same time, studies have extensively demonstrated that such individuals often have impaired PFC functioning associated with early trauma, neglect, head injuries, substance abuse, or developmental impairments. A weakened PFC has insufficient ability to manage or inhibit the emotional output of the amygdala, which results in a person's inability to slow down, think, or make conscious choices when confronted emotionally.

Poor communication between the PFC and amygdala, such as reduced fronto-limbic connectivity, is a significant contributor to this problem. When people's "thinking brains" and "emotional brains" are not in sync, they are more likely to misinterpret intent, escalate conflicts, and act impulsively. Such neural disruptions are especially prevalent among those who have a history of childhood maltreatment, given the influence of early stress on brain development and impaired emotional regulation pathways.

Hyperreactivity of the amygdala, combined with deficits in the prefrontal regions and impaired neural connectivity, forms a neurological setting in which impulsive aggression becomes more probable. That doesn't mean the brain "forces" someone to commit a crime, but it does imply that their biology is leading to much greater difficulty in regulating emotional impulses. Understanding these neural patterns is crucial for developing effective risk assessments, interventions, and rehabilitation programs that help offenders reinforce self-control, emotional stability, and decision-making.

The role of neurocriminology

Neurocriminology helps provide a bridge between neuroscience and criminal behavior by investigating how variations in brain structure, function, and neural development underlie antisocial or violent acts. Traditionally, criminology has come from a sociological, psychological, and environmental basis of reasoning. Neurocriminology brings in a biological and neurological perspective, demonstrating that specific patterns of criminal behavior, in particular, impulsive and emotionally reactive crimes, are linked to quantifiable differences in brain functioning. In this way, the field helps illustrate why some people react aggressively, why others cannot control their impulses, and why certain crimes happen on the spur of the moment without forethought.

Perhaps one of the major contributions of neurocriminology is its ability to identify neurobiological risk factors for violent behavior. Using imaging techniques like fMRI, PET scans, and structural MRI, studies have reported abnormalities consistently in areas such as the amygdala and prefrontal cortex among offenders. For instance, individuals who exhibit overly active amygdala responses are more sensitive to perceived threats, which predisposes them toward acting aggressively. On the other hand, lower activity or structural deficits in the prefrontal cortex are known to disrupt self-regulation, moral reasoning, and decision-making. By recognizing these patterns, neurocriminology provides a scientific explanation for behaviours previously blamed on poor judgment or deliberate intent.

Another important role of neurocriminology involves its bearing on risk assessment and rehabilitation planning. Understanding an offender's neurological profile helps forensic psychologists determine whether the individual is more prone to impulsive violence, emotional dysregulation, or impaired self-control. These insights may inform treatment plans and tailor interventions to the offender's specific neural vulnerabilities. For example, offenders with prefrontal deficits would especially benefit from cognitive strengthening programs, impulse-control therapies, and emotional regulation training, while those suffering from trauma-induced limbic hyperreactivity should be treated with trauma-focused or somatic therapies. Neurocriminology, therefore, favors an increasingly individual approach to rehabilitation rather than a uniform approach.

Neurocriminology has also started to shape the legal and ethical debates on criminal responsibility, culpability, and sentencing. Neuroscience does not excuse crimes but places the offenders' actions in a context that details their internal constraints, such as deficiencies in impulse control, threat perception, or executive functioning. Courts are now taking greater consideration of neuroscientific evidence during mitigation, particularly in the cases of juveniles, those suffering traumatic brain injuries, or offenders with histories of trauma. This integration of brain science encourages more humane and informed legal decisions, balancing accountability with psychological and biological realities.

Finally, neurocriminology stresses the need for early prevention. Because most neural vulnerabilities develop in childhood due to trauma, neglect, malnutrition, or chronic stress, early interventions can greatly reduce the risk of later criminal behavior. Programs focused on trauma recovery, emotional development, parental support, and early mental health screening offer possibilities to enhance prefrontal functioning and reduce amygdala hyperreactivity. Thus, neurocriminology explains not only crime but also guides society toward prevention strategies with scientific evidence as a foundation.

Shadow psychology: Jungian theory applied to serial offenders

Jungian psychology is unique and powerful in its perspective on criminal behavior by focusing on the parts of personality that are unconscious, hidden, and unaccepted. Neuroscience and trauma research explain crime through biological and emotional factors, respectively. Jungian theory, in contrast, focuses on both symbolic and psychological meanings of violent or compulsive acts. According to Carl Jung, each of us has a "shadow" -a reservoir of repressed emotion, instinct, desire, and traits which the conscious self denies or tries to suppress. When these denied aspects of personality have been driven too deep within the unconscious, they may at last break through to manifest in ways that are destructive or damaging.

This becomes clearer in the context of Jung's theory, which explains why certain individuals commit crimes in repetitive or symbolic patterning, why their crimes appear emotionally charged or ritualistic, and why offenders sometimes seem disconnected from their actions. The shadow psychology postulates that violent or antisocial behaviors may emerge when unresolved inner conflicts, traumatic memories, or denied emotional needs break through to the surface. This perspective provides an insight into the psychological complications of offenders whose actions cannot be explained by external factors.

Jung's concept of the shadow

Jung used the term “shadow” to refer to that part of the personality that lies hidden from view: the aspects of ourselves we find deplorable and deny because they pose a threat to our idealized self-image. These might include aggressive impulses, shameful emotions, forbidden desires, vulnerability, fear, or unresolved trauma. Rather than disappear, such unwanted material is stored in the unconscious mind, influencing our thoughts and actions indirectly. The more rigid or heavily defended the conscious mind, that is, the more one's personality, for example, pretending to be overly strong, perfect, moral, or in control, the stronger the shadow becomes.

In offenders, the shadow often contains intense feelings and impulses derived from earlier trauma, humiliation, or fear. Because the individual represses these painful experiences or character traits, they can suddenly burst forth as explosive anger, cruelty, or impulsive violence. Jung believed that when an individual does not consciously integrate his shadow, the shadow "acts out" through behaviour, often in ways that shock the person as much as others. This can explain why some offenders report feeling like a "different person" during violent episodes or struggle to understand their own motivations. In such cases, the crime becomes an expression of the shadow self, operating outside conscious control.

Shadow traits manifestation in offenders

The shadow does not appear haphazardly; it comes through patterns that show the offender's inner conflicts and unresolved emotional wounds. In violent offenders, much of this shadow material is manifested through projection, a process in which an individual attributes his or her own unwanted characteristics or fears to others. For example, the offender might feel vulnerable and view others as threatening, acting in self-defense with aggression. This process of projection escalates into Violence might ensue when emotional triggers activate deep-seated insecurities or unresolved trauma.

Another way in which the shadow manifests is through repetition compulsion, whereby individuals unconsciously redo those painful or traumatic situations from their past. They may act out patterns of abuse, domination, or control that they themselves have experienced as children, by either taking the role of the aggressor or finding themselves in situations that resemble their earlier environment. This mechanism would, therefore, explain why certain offenders show consistent victim profiles, ritualistic patterns of crime, or repeat offences despite conscious desires not to commit further crimes. Their behaviour is driven not by rational planning but by unconscious psychological forces seeking expression or resolution.

In some offenders, the shadow and identity have become enmeshed, and the socially acceptable self becomes dissociated from its hidden, destructive counterpart. This concept of a double identity is very familiar in offenders who lead so-called double lives, appearing calm, polite, or successful to outsiders but privately committing violent or antisocial acts. According to the Jungian approach, when the shadow is too strong, it breaks through the control of the ego, with instincts or trauma-directed impulses taking the upper hand in driving the behavior. In this perspective, compulsive, ritualistic, or serial offending-the type where specific symbolic themes in the crimes reflect inner conflicts of the offender-can be explained.

Serial offenders typically exhibit the following characteristics:

- Repressed desires that evolve into dark fantasies

- Dissociation between their public persona and hidden impulses

- Projection of their own internal conflicts onto victims

Why serial offenders are psychologically "split."

Serial offenders almost always manifest a sharp psychological division between their outer personality and the inner, violent behavior-a concept that Jungian theory helps explain as a severe ego-shadow split. Most serial offenders appear calm, intelligent, polite, or socially well-adjusted on the surface, holding steady jobs, pursuing relationships, or fitting unobtrusively into society. Yet beneath this façade lies a shadow filled with repressed desires, unresolved trauma, and potent aggressive impulses. Such a split occurs because the conscious ego cannot tolerate recognizing the darker aspects of the personality, and thus pushes them into the unconscious, where energy is building up and is influencing behavior covertly.

The psychological splitting is usually related to early developmental trauma, emotional neglect, or inconsistent caregiving. When a small child grows up in a family where the expression of fear, anger, vulnerability, or need is threatened and/or shamed, the psyche learns to "split off" to survive these emotions. A false self develops, presenting the child as strong, compliant, or emotionally numb, while the real emotional turmoil gets buried. As the individual matures, the false self becomes the outward personality while the hidden shadow grows all the more intense and eventually manifests through compulsive or violent behavior. In serial offenders, violent acts may be an unconscious release of repressed emotions, giving them a temporary sense of power, control, or identity that their conscious self does not possess. Another reason serial offenders appear split is due to dissociation, a psychological defense mechanism that separates one's emotional experience from one's conscious self. Dissociation allows offenders to commit violent acts without fully registering the emotional impact or moral weight of their behaviour. Many serial offenders describe feeling detached, numb, or "not themselves" during the offense, as if another part of them had taken over. This dissociative state explains how they commit extreme violence and then afterwards appear calm, organized, or flat emotionally. It also accounts for the double lives they lead socially.

Acceptable persona during the day and a predatory one at night. According to the Jungian concept, the duality is explained by the shadow overpowering the ego in cases of a non-integrated ego. The ego is representative of the conscious identity, the rational, social, rule-following self, while the shadow houses the disowned instincts, rage, fantasies, and desires. In normal individuals, communication occurs between both the ego and the shadow, allowing unacceptable impulses to be acknowledged and safely processed. In serial offenders, this integration has not occurred. Instead of processing the shadow, it is dealt with as an internal, separate entity that influences behavior through fantasies, compulsions, or intrusive urges. Accordingly, when specific emotional triggers come along-shame, rejection, stress, or even a symbolic reminder of some particular trauma-the shadow may take over and generate violent enactments. This psychological split also explains the ritualistic and repetitive nature of the serial crimes; each offense is not only a violent act but also an unconscious attempt to solve inner conflicts, replay trauma, or fulfill shadow-driven fantasies. Since the latent emotional wound remains unhealed, the compulsion returns, driving the offender to repeat the behavior. In this way, such a cycle reinforces the split between the "public self" and "hidden self," making the split even more pronounced over time. In short, serial offenders are psychologically "split" because their conscious personality and unconscious shadow operate as two separate systems: the social normalcy of the public self and the driving force of hidden fantasies and violent acts.

Powered by the shadow, this division arises because of early trauma, repression of emotions, dissociation, and failure to integrate the dark aspects of the psyche. Understanding such division is essential in such concepts as forensic profiling, risk assessment, and interpreting the inner world of offenders whose actions cannot be understood from surface-level behaviour alone.

Based on the theoretical framework, mechanisms, and empirical directions outlined in our article, testable research hypotheses that directly align with this paper are given below:

Primary Testable Hypothesis (core) H1 (Main Hypothesis): Individuals with a documented history of early childhood trauma will exhibit significantly higher levels of impulsive or reactive violent behaviour in adulthood, and this relationship will be mediated by impaired emotional regulation and heightened limbic (amygdala) reactivity.

Testability: Childhood trauma severity (ACE score or trauma inventory)

Mediators: Emotional regulation deficits, amygdala reactivity

DV: Frequency or severity of impulsive violent acts

Neurocriminology-Based Hypotheses H2:

Offenders with early developmental trauma will show increased amygdala activation and reduced prefrontal cortex (PFC) activation during threat-related tasks compared to non-traumatized offenders.

Testability: fMRI threat-processing paradigms

Group comparison (trauma vs. non-trauma offenders) H3:

Reduced functional connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala will predict greater impulsivity and loss of behavioural control during emotionally charged situations.

Testability: Neuroimaging connectivity analysis

Behavioural impulsivity scales or laboratory aggression tasks

Subconscious / Implicit Memory Hypotheses H4:

Exposure to trauma-related emotional cues will elicit stronger automatic physiological responses (e.g., heart rate, skin conductance) in violent offenders than in non-violent offenders, independent of conscious threat appraisal.

Testability: Psychophysiological measures

Subliminal or affective priming tasks.

Repressed trauma as a driver of criminal compulsion

Repressed trauma plays a central role in shaping the emotional and behavioral patterns that later contribute to criminal behaviour. When the traumatic experiences of abuse, neglect, humiliation, or abandonment have taken place in one's childhood, the child is often unprepared psychologically to deal with or understand these experiences. As a mechanism of survival, the psyche pushes down the overwhelming emotions, memories, and sensations associated with the trauma into the unconscious. This repression, though it is clearly protective for the child in the short term, leaves deep psychological wounds that continue to influence behavior long into adulthood. Later in life, these unresolved emotional wounds can manifest as compulsive aggression, impulsive violence, dissociation, and reenactment of the original trauma. Adults who have had repressed trauma act out with disproportionate emotional intensity relative to situations. A relatively minor conflict, rejection, or threat may unconsciously trigger old traumatic memories and feelings of fear, shame, helplessness, or rage. Because such reactions do indeed stem from the unconscious rather than from any conscious awareness, individuals often cannot understand or explain their own behavior. Many offenders report violent episodes as "automatic", "out of character", or "as if something took over", reflecting the dominance of trauma- driven affective states that bypass rational thinking. In this respect, repressed trauma can become a silent mover in shaping a criminal career trajectory.

Understanding repression in criminal psychology

One of the most important concepts in criminal psychology is repression because it details how an individual can look functional on the surface yet carry unresolved emotional wounds in the unconscious mind. In instances of trauma, especially when it occurs during childhood, the mind cannot deal with the fear, shame, or pain associated with the event. The brain represses these emotions out of consciousness as a way of self-protection from such emotional overload. The problem with repression, however, is that it does not remove the trauma; it buries it. The memory, and all the emotions attached to it, remain active in the subconscious, influencing perceptions, behaviours, and emotional reactions without the person realizing the connection. Thus, an adult offender who is reacting violently to a minor provocation may actually be responding to emotions that have their root in childhood trauma and not to the present situation. Repressed trauma also distorts threat perception, making people hyperreactive to stress, conflict, or rejection. Because the trauma is unconscious, the individual cannot explain or understand the origin of his intense reactions, entering into a cycle where subconscious wounds drive conscious behaviour. In this way, repression is not a passive psychological state but an active force shaping emotional regulation, personality, and behaviour, including criminal acts.

Trauma-driven criminal patterns

Individuals who have been suffering from repressed trauma tend to produce a behavioural pattern that is markedly repetitive, intense, and emotional in nature. Among these highly established patterns is repetition compulsion, whereby the individual unconsciously repeats some of the past traumas in relationships, choices, or violent actions. For example, one who has grown up in a violent household may continuously be involved in aggressive confrontations or abusive relationships, either as a victim or an offender, simply because the trauma has created a “template” with which he interprets and responds to interpersonal dynamics. Another more common pattern is emotional numbness, in which the person may lose contact with his own feelings as a method of psychological survival. This kind of emotional deadness may result in risk-taking, thrill-seeking behavior, substance abuse, or violent acts simply to break through this numbness and feel a sense of control, excitement, or power. Likewise, many offenders convert unresolved inner pain into external aggression as a coping strategy. Because expressing vulnerability feels dangerous or unacceptable, aggression becomes a substitute for emotional expression. This is why people who feel worthless, rejected, or ashamed often react with explosive rage, even when the immediate trigger seems trivial. These trauma-driven patterns reveal that in many instances, the cause of aggression lies in having incurred some forms of emotional injury rather than any conscious intentions of malice.

Trauma and compulsive violent behaviour

A large body of forensic and clinical research thus demonstrates that unresolved trauma can be a direct cause of the compulsive, repetitive, and uncontrollable forms of violent behaviour. In most offenders, the violent act is not driven by a wish to injure or destroy others but is instead a subconscious effort at discharging an overwhelming tension, escaping from emotional pain, or reenacting unresolved childhood experiences. Domestic violence, impulsive assaults, sexual offenses, stalking, and rage attacks are crimes most likely to happen when repressed trauma is triggered by emotional cues such as rejection, humiliation, loss of control, or perceived disrespect. When the trauma that is buried erupts after being activated by these cues, the individual is overwhelmed by a surge of emotional intensity that surpasses rational thinking and impulse control. This might force him/her into a dissociative or hyperaroused state in which he/she automatically acts aggressively or destructively. Importantly, these individuals often report feeling “out of their body,” “not themselves,” or unable to control their actions during the offense. This further suggests how trauma may resurface in the form of compelling behaviors rather than conscious choices. Violent acts are symbolic expressions of unresolved fear, rage, or shame rather than deliberate acts of cruelty. Absent proper treatment for trauma, such compulsions will recur, producing a cycle of violence driven by subconscious emotional wounds.

Ethical and forensic implications of subconscious processes in criminal behaviour

Forensic psychologists, the courts, and rehabilitation programs need to recognize the impact of buried trauma. Traditional forensic assessments commonly focus on criminal history, cognitive functioning, and premeditated motives while bypassing the emotional and subconscious motives for violent behavior. On the other hand, trauma-informed forensic assessments search for early experiences, concealed triggers, dissociative tendencies, and affective vulnerabilities that underpin behavior. Once such elements are identified, differentiation can be made between a premeditated and intentional crime and an impulsive, trauma-driven act emanating from emotional dysregulation. The latter is critical to proper risk assessment, treatment planning, and sentencing. In this vein, trauma-informed rehabilitation far surpasses cognitive or behavioral treatment alone. Those programs that have incorporated trauma-focused therapy with emotion regulation techniques, somatic processing, and memory reconsolidation methods have reported significant decreases in recidivism. By enabling offenders to process their trauma, gain insight, and acquire healthier self-regulation strategies, the justice system can interrupt the cycle of violence and ensure long-term behavioral change. Trauma-informed practice shifts the paradigm from punishment to healing the root cause, making the process of rehabilitation both more effective and more humane.

Ethical implications: One of the primary ethical concerns involves the concept of criminal responsibility. The reviewed literature suggests that many offences—particularly impulsive and emotionally reactive crimes—are initiated by subconscious processes shaped by early trauma and neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities. From an ethical standpoint, this challenges the traditional assumption that all criminal acts arise from fully conscious, rational choice.

However, acknowledging subconscious influences does not ethically justify excusing criminal behaviour. Rather, it introduces a more nuanced understanding of moral agency. Offenders may retain legal responsibility for their actions while simultaneously experiencing diminished emotional regulation, impaired threat perception, or reduced impulse control during the offence. Ethically, this supports a graded view of responsibility, where intent and capacity are evaluated along a continuum rather than as an absolute.

Risk of determinism and stigmatization: A further ethical risk lies in biological or psychological determinism. Overemphasizing subconscious or neurobiological explanations may inadvertently promote the belief that offenders are "hardwired" to commit crime. Such deterministic interpretations risk stigmatizing individuals with trauma histories or neurological vulnerabilities, potentially leading to discrimination, excessive surveillance, or unjust preventive detention.

An ethically sound application requires careful framing: subconscious mechanisms increase vulnerability but do not predetermine criminal behaviour. Environmental context, learning, personal values, and access to intervention all remain critical moderators. Forensic professionals must therefore avoid reductionist explanations that portray offenders as irreversibly dangerous.

Informed consent and psychological evaluation: Trauma-informed and neuropsychological assessments often involve probing deeply personal histories, dissociative experiences, and implicit emotional responses. Ethical practice demands strict adherence to informed consent, confidentiality, and psychological safety. In custodial or forensic settings, true informed consent can be compromised due to power imbalances, perceived coercion, or misunderstanding of how assessment data may be used in court.

Professionals have an ethical obligation to clearly explain the purpose, scope, and potential legal consequences of such evaluations. Failure to do so risks retraumatization, misuse of sensitive psychological information, and erosion of trust in forensic mental health services.

Interpretation of intent and mens rea: Subconscious-driven behaviour complicates traditional legal concepts such as mens rea. When actions are initiated through rapid limbic activation before conscious awareness, determining intent becomes more complex. This is particularly relevant in cases of sudden violence, domestic assaults, or rage-driven offences. Forensic psychology contributes by distinguishing between:

* Premeditated, goal-directed violence

* Impulsive, trauma-triggered reactions

Such distinctions assist courts in evaluating degrees of culpability, sentencing proportionality, and the appropriateness of mitigation without negating accountability.

Reliability of self-report and memory evidence: Another forensic challenge concerns the reliability of offenders’ narratives. Subconscious processes, dissociation, and implicit memory mean that individuals may genuinely struggle to articulate motives or recall offence-related details accurately. While this does not imply deception, it complicates credibility assessments. Forensic evaluators must therefore integrate behavioural evidence, collateral information, and psychological testing rather than relying solely on self-report. Courts must also exercise caution when interpreting memory gaps or emotional detachment as intentional evasion.

The increasing introduction of neuroimaging and neuroscientific data in legal proceedings raises significant forensic and ethical questions. While such evidence may contextualize impulsivity or impaired regulation, it remains probabilistic rather than determinative. Brain abnormalities or trauma markers cannot reliably predict individual criminal acts.

Overreliance on neuroscientific findings risks overstating their explanatory power and may mislead legal decision-makers. Forensic use of such evidence must therefore be conservative, supplementary, and clearly communicated in terms of limitations.

Limitations of informed and trauma-based approaches: Despite their value, informed approaches grounded in subconscious processes face several limitations.

Methodological limitations: Much of the evidence linking childhood trauma, subconscious memory, and criminal behaviour is correlational. While strong associations exist, causation cannot always be definitively established. Not all individuals exposed to trauma engage in criminal behaviour, and not all offenders have identifiable trauma histories. Additionally, subconscious processes are inherently difficult to measure. Neuroimaging, psychodynamic formulations, and trauma assessments rely on inference rather than direct observation, limiting their precision in forensic decision-making.

Legal system constraints: Legal systems are structured around clear categories of intent, responsibility, and proof. Subconscious and pre-conscious explanations do not always fit neatly within these frameworks. Courts require observable evidence and standardized criteria, whereas trauma-informed insights are often individualized and interpretive. As a result, there is a risk that such approaches may be inconsistently applied, depending on judicial familiarity, expert quality, or available resources.

Resource and implementation barriers: Trauma-informed forensic assessments and rehabilitation programs require trained professionals, time, and institutional support. Many correctional systems lack the infrastructure to implement comprehensive psychological screening or long-term therapeutic interventions. Without proper implementation, informed approaches may remain theoretical rather than impactful.

Ethical balance and future directions: The ethical challenge lies in balancing compassion with accountability, scientific insight with legal practicality, and individualized understanding with public safety. Subconscious-based explanations should inform—not replace—traditional forensic evaluation. When used responsibly, they enhance fairness in sentencing, improve risk assessment, and guide effective rehabilitation. Future forensic practice must integrate neuroscience, trauma psychology, and legal standards through clear ethical guidelines, rigorous training, and ongoing research. By recognizing both the power and the limits of informed approaches, the justice system can move toward responses that are not only evidence-based but also ethically grounded and socially responsible.

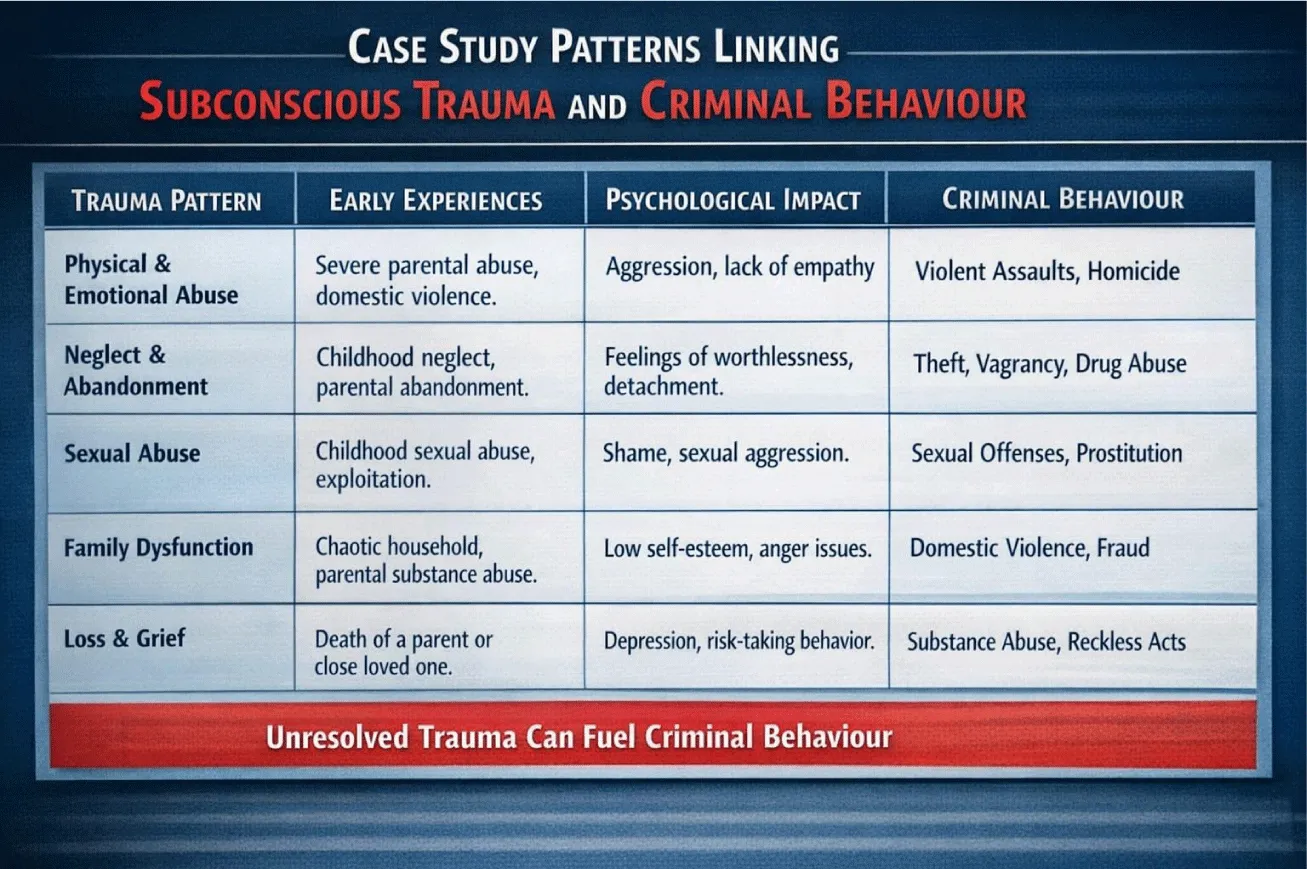

Case-study patterns linking subconscious trauma and criminal behaviour

Rehabilitation of offenders is most effective when it goes beyond surface-level behavioural correction to deeper levels, addressing psychological wounds and subconscious patterns that drive criminal behaviour. Most of the offenders, especially impulsive and violent offenders, carry unresolved trauma, dysfunctional emotional regulation patterns, and maladaptive coping mechanisms that are not correctable by punishment or cognitive exercises alone. Modern forensic psychology emphasizes the need for trauma-informed, neurobiologically-informed interventions that aim at healing emotional wounds, rebuilding self-regulation, and reducing internal triggers of criminal behaviour. Effective rehabilitation recognizes that lasting behavioural change relies on emotional healing, heightened self-awareness, and a restructuring of subconscious memory patterns.

Principles of trauma-informed rehabilitation

Trauma-informed rehabilitation is underpinned by the knowledge that a large portion of criminals.

The behaviour emanates from unresolved emotional pain, repressed memories, and maladaptive survival strategies acquired in childhood. The main principle in this type of rehabilitation is to treat the cause and not just the symptoms of criminal behaviour. Many offenders are not violent out of malice but act from a place of emotional triggers, dissociation, or subconscious trauma patterns that override it is through rational thought that rehabilitation, therefore, has to create a psychologically safe environment where offenders can feel free to explore their emotions without fear of judgment or punitive action.

Trauma-informed practice focuses on helping the offender understand their triggers, identify subconscious emotional patterns, and learn healthier ways of coping. It involves making them realize how fear, shame, abandonment, or humiliation may underpin their behaviour. The rehabilitation process also needs to direct its attention to emotional regulation, stress management, and rebuilding secure internal attachment systems. Trauma-informed principles capitalize on the emotional cause of crime, thereby fostering empathy, self-awareness, and accountability-things that are very crucial for long-term behaviour changes.

Effective therapeutic interventions

There are several evidence-based therapeutic approaches offering hope in reducing trauma-driven violence and impulsive offending by rewiring emotional responses, healing subconscious memory patterns, and strengthening self-control.

a. Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT): This approach allows offenders to process traumatic experiences, challenge distorted beliefs, and understand how their past influences their behaviour. It is particularly suitable for offenders demonstrating a history of abuse, neglect, or chronic stress.

b. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): EMDR targets traumas stored in the subconscious memory system. This indeed decreases emotional intensity, reactivity, and trigger-based aggression by reprocessing traumatic memories. Many offenders indeed show significant improvements in emotional regulation post-EMDR.

c. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): This treatment teaches emotional regulation, distress tolerance, mindfulness, and interpersonal effectiveness. DBT is very effective with offenders who have problems with impulse control, self-harm behaviours, and mood instability.

d. Somatic and body-based therapies: Since trauma often resides in the body, somatic therapies help offenders learn to release tension, reduce hyperarousal, and recognize the physical signs of emotional activation to reduce the risk of dissociative or impulsive reactions.

e. Memory reconsolidation approaches: These therapies aim to update the traumatic memory patterns through the reactivation of old memories, thus incorporating new emotional experiences. Techniques of reconsolidation have shown promising results in reducing compulsive, trauma-driven behaviors.

f. Mindfulness and meditation-based programs: These interventions heighten self-awareness, reduce impulsivity, and develop the executive functioning of the brain. They provide a pause for offenders before reacting, which reduces aggression and emotional reactivity. Changes achieved through such interventions are deep and long-lasting rather than superficial behavioral compliance, as they address the subconscious and emotional systems directly.

Application in forensic and correctional settings

Trauma-informed rehabilitation in prisons and forensic institutions requires a shift from punitive models toward more therapeutic, developmental, and strength-based perspectives. Correctional facilities must make provision for trauma history screening as a part of the assessment, along with dissociation, emotional dysregulation, and neurological impairments. Such awareness of the psychological background of an offender enables the practitioner to devise an individual rehabilitation plan that caters specifically to certain triggers and vulnerabilities.

In practice, trauma-informed programs include structured therapy sessions, emotional regulation groups, mindfulness training, and individual counselling targeted at the specific neuropsychological needs of each offender. Staff must be trained to recognize trauma responses and not interpret them as defiance or manipulation. Providing a predictable, respectful, and psychologically safe environment reduces trauma reactivation and improves treatment outcomes.

Consistent trauma-focused rehabilitation enables offenders to develop healthier coping strategies and to be more emotionally regulated, with better insight into their behaviours. Outcomes associated with this are significantly lower recidivism rates and long-term reintegration into the community by offenders. Finally, trauma-informed correctional practice transforms rehabilitation from a punishment-oriented process to a profoundly healing process, as it identifies the emotional roots of criminal behaviour rather than its symptoms [12-50].

This review shows that criminal behaviour in general, and impulsive-violent and emotionally reactive offenses in particular, cannot be fully understood using traditional criminological theories emphasizing rational choice, social factors, or conscious intent. Rather, a developing body of psychological, neuroscientific and forensic evidence establishes that the subconscious mind lies at the very center of criminal behaviour. Early childhood trauma, insecure attachment, emotional neglect, and adverse developmental experiences are stored not as logical memories but as implicit emotional patterns that continue to influence behaviour long into adulthood. These subconscious imprints resurface in the form of heightened reactivity, impaired emotional regulation, distorted threat perception, and compulsive reenactment of past trauma.

Neurocriminology further illustrates how emotional systems of the brain often fire before conscious reasoning can step in. Limbic hyperactivity in structures like the amygdala, combined with Underdeveloped or impaired prefrontal control systems, is a biological vulnerability in some individuals that predisposes them to impulsive or violent reactions. These findings undermine any simplistic assumptions about free will and intentionality in crime by underlining the view that behaviour emerges as part of a complex interplay of unconscious processes, neural development, and unresolved emotional conflicts. The psychodynamic and Jungian perspectives further the understanding by highlighting how repressed desires, unresolved trauma, and the unintegrated "shadow" self can manifest in harmful or antisocial ways. Many offenders have deep psychological splits between their outward persona and their hidden emotional world. Violent acts can be an expression of buried shame, fear, anger, or unmet Emotional needs that were never brought into conscious awareness and healed. Repetition compulsion, dissociation, and unconscious scripts further explain why some offenders commit similar crimes repeatedly or feel "taken over" during violent episodes. From the perspective of these findings, punishment itself cannot resolve the root causes underlying trauma-driven criminal behaviour. Trauma-informed practice rehabilitation, therapies of memory reconsolidation, emotional-regulation training, and body-based interventions all provide more propitious pathways toward reducing recidivism and promoting long-term behaviour modification. Helping the offenders work through unresolved traumas, understand their emotional patterns, and develop self-control, rehabilitation may become not only corrective but also healing. Approaches of this kind recognize the offender as a product of psychological wounds no less than conscious choices and prepare the ground for a more humane, effective, and scientifically sound response to crime. Eventually, such an understanding of the Influence of subconscious memory will reshape the whole concept of forensic science, criminology, and legal practice. It encourages society to move away from merely punitive systems and towards models that integrate psychological healing, neuroscience, and early intervention. We will be able to reduce recidivism, foster healthier communities, and shape a justice system that is both it should be compassionate and evidence-driven, and address the emotional and neurological roots of violence. The future of criminology consists of recognition of the fact that very often, crime is not a rational act but a symptom of deeper, hidden struggles within the human mind.

- Schacter DL. Searching for memory. New York: Basic Books; 1996. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1996-97906-000

- Siegel DJ. The developing mind. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. Available from: https://books.google.co.in/books/about/The_Developing_Mind_Second_Edition.html?id=lF-BA_cdEO0C&redir_esc=y

- van der Kolk BA. The body keeps the score. New York: Viking; 2014. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Body_Keeps_the_Score

- LeDoux J. Anxious: Using the brain to understand and treat fear and anxiety. New York: Viking; 2015. Available from: https://cmc.marmot.org/Record/.b49001401

- Perry BD. Examining child maltreatment. J Pediatr. 2009;153(6):S6–S12. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020903004350?urlappend=%3Futm_source%3Dresearchgate.net%26utm_medium%3Darticle

- Teicher MH, Samson JA. Childhood maltreatment and brain development. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(8):578–597.

- Bloom SL. Creating sanctuary: Toward the evolution of sane societies. New York: Routledge; 2013. Available from: https://www.routledge.com/Creating-Sanctuary-Toward-the-Evolution-of-Sane-Societies-Revised-Edition/Bloom/p/book/9780415821094

- Schore AN. The effects of early relational trauma. Infant Ment Health J. 2001;22(1–2):201–269. Available from: https://www.allanschore.com/pdf/SchoreIMHJTrauma01.pdf

- Ecker B. Memory reconsolidation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;63:17–85.

- Main M, Solomon J. Disorganized attachment. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990;121–160.

- Herman JL. Trauma and recovery. New York: Basic Books; 1992. Available from: https://beyondthetemple.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/herman_trauma-and-recovery-1.pdf

- Andrews DA, Bonta J. The psychology of criminal conduct. 6th ed. New York: Routledge; 2019.

- Bargh JA, Morsella E. The unconscious mind. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3(1):73–79. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00064.x

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books; 1988. Available from: https://www.increaseproject.eu/images/DOWNLOADS/IO2/HU/CURR_M4-A13_Bowlby_(EN-only)_20170920_HU_final.pdf

- Bremner JD. Traumatic stress: Effects on the brain. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):445–461. Available from: https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2006.8.4/jbremner

- Bushman BJ, Anderson CA. Is it time to pull the plug on the hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychol Rev. 2001;108(1):273–279. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.273

- Cacioppo JT, Freberg L. Discovering psychology: The science of mind. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2018. Available from: https://archive.org/details/discoveringpsych0000caci_a0y1

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:409–438. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029

- Craik FIM, Squire LR. Memory and the brain. Sci Am. 2004;290(1):76–83.

- Damasio A. Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Putnam; 1994. Available from: https://ahandfulofleaves.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/descartes-error_antonio-damasio.pdf

- De Bellis MD, Zisk A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2014;23(2):185–222. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.002

- Dutton DG. The abusive personality: Violence and control in intimate relationships. New York: Guilford Press; 2007.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Fonagy P, Target M. Psychoanalytic theories: Perspectives from developmental psychopathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183(6):567. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.183.6.567-a

- Freud S. Beyond the pleasure principle. In: Strachey J, editor. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. 18. London: Hogarth Press. 1955;1–64. Available from: https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Freud_Beyond_P_P.pdf

- Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(4):539–579. Available from: https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/bul-1284539.pdf

- Gilligan J. Violence. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons; 2000.

- Goleman D. Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books; 1995.

- Hare RD. Without conscience: The disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. Available from: https://www.guilford.com/books/Without-Conscience/Robert-Hare/9781572304512

- James N, Raine A. The criminal brain. Annu Rev Criminol. 2018;1:29–49.

- Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered assumptions. New York: Free Press; 1992. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=775382

- Jung CG. Aion: Research into the phenomenology of the self. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press; 1959. Available from: https://search.worldcat.org/title/Aion-%3A-researches-into-the-phenomenology-of-the-self/oclc/1244225940

- Jung CG. The archetypes and the collective unconscious. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press; 1968. Available from: https://search.worldcat.org/title/The-archetypes-and-the-collective-unconscious/oclc/1148028326

- Kandel ER. In search of memory. New York: W.W. Norton; 2006. Available from: https://wwnorton.com/books/In-Search-of-Memory/9780393329377

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of neural science. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Kerns JG. Emotion–cognition interactions. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(2):311–352.

- LeDoux JE. The emotional brain. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1996.

- Linehan MM. DBT skills training manual. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2015. Available from: https://www.guilford.com/add/linehan7_old/lin-p-1teaching.pdf?t=1

- McCrory E, De Brito SA, Viding E. The impact of childhood maltreatment: a review of neurobiological and genetic factors. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:48. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00048

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2016. Available from: https://www.guilford.com/books/Attachment-in-Adulthood/Mikulincer-Shaver/9781462533817

- Miller A. The drama of the gifted child. New York: Basic Books; 1984. Available from: https://dn720006.ca.archive.org/0/items/the-drama-of-the-gifted-child/The%20Drama%20of%20the%20Gifted%20Child.pdf

- Ogden P, Minton K, Pain C. Trauma and the body. New York: W.W. Norton; 2006. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-12273-000

- Perry BD, Szalavitz M. The boy who was raised as a dog. New York: Basic Books; 2006.

- Porges S. The polyvagal theory. New York: W.W. Norton; 2011.

- Raine A. The anatomy of violence: The biological roots of crime. New York: Pantheon Books; 2013. Available from: https://clcjbooks.rutgers.edu/books/anatomy-of-violence/

- Schore AN. The science of the art of psychotherapy. New York: W.W. Norton; 2012.

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Mashek DJ. Moral emotions and crime. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:349–374.

- van IJzendoorn MH. Attachment and deprivation. Child Dev. 1997;68(4):703–717.

- Widom CS, Maxfield MG. An update on the cycle of violence. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 2001. Available from: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/184894.pdf

- Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar M. Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=80017